What Does It Feel Like to Be a Painting of Rebekka Löffler?

For a while, I have been asking myself what does it feel like to be an object. I know it is nonsense to try to overcome the anthropocentrism that defines us as a species. It is wishful thinking, an impossible transmutation of matter that turns my body into something else, into a thing. Often, this wish aims at common things, those we despise when we tag them as merchandise: a cup of coffee, a chair, a dish, a screwdriver, a mirror or a vase. Those are mass-produced objects that allow us to use the concept of copy, although this does not quite convey the concrete reality that it produces. When my ego is at its finest, I ask myself what does it feel like to be an artwork, that object different from the rest, with a higher status, one that emanates from its alleged unique condition. For many the uniqueness of artworks derives from an intentional misunderstanding, the result of removing them from the concept of industrial production, even though they are constructed with materials that come from a part of the economy in which things are, above all, products. Artworks are not products, but the materials in them are. Artworks are unique objects made from mass-produced ones. Maybe, it is as simple and complicated as to think that the unique character of artworks spring from the unique character of those that produce them, artists, who can indeed be transformed into the object that they create, or, at least, live their lives through them in an attempt to change the world. And with this statement, I return to the anthropocentrism that I hoped to avoid before.

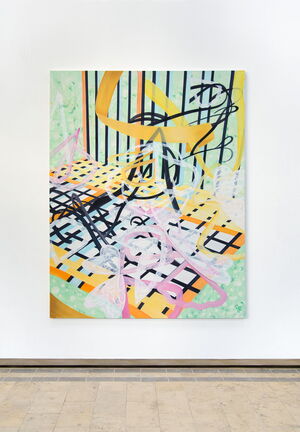

What does it feel like to be a painting of Rebekka Löffler? What does it feel like to hang from the wall, waiting for the perfect viewer, who will stop and look closely at each detail, hoping to understand what is seen and hoping to be part of a cognitive illusion? What does it feel like to be an end result, but also to be part of a bigger process in which color aims to be daring? To become a painting is an opportunity to be an object that turns imagination into something real, physical. It is an anachronistic object that embodies both the resistance of a medium versus the accelerations of the mediated image, and the inexhaustible source of a permanence will. This is a space in which life shows itself in a different way —that of the artist, that of multiple viewers, even that of those that do not know the painting exists—, through layers of painting that overlap each other and are the result of mutual reliance, the same reliance that upholds the structures that make the real function even when it disappoints us and we want to escape it. It is an extension of Flatland, two-dimensional and tri-dimensional at the same time, a territory where color shows itself through representation. It is like an idea that spreads physically and cannot —or does not want to— acquiesce to conventional discourse. It is a space capable of delivering an uncanny effect where the conventional and the extraordinary, what is known to exist and what does not yet exist, meet. It is a system of human and non-human interactions, an extension of life that makes that system, and its constitutive materials, happen. It is a fragment of alien life with common features. It is a static organism that begins its movements through eye contact, a multi-stable perceptive phenomenon. To be a painting is the materialization of a commitment, that with the act of painting itself. It is color taking place in space, resisting all chromophobic rhetoric. It is the material answer given by the joyful color insurrection, an action that, not only goes across time, but also captures it. It is the construct of a possibility that inhabits and expands the canvas. It is an image within which perceptive experience means more than signs. It is an answer in search of a question, an appearance that can never mislead.

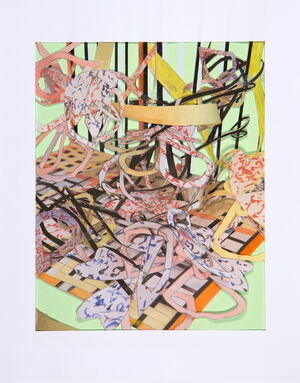

The interaction system that Rebekka Löffler’s paintings allow can transcend the pictorial medium itself. The act of painting is something that already happens outside the canvas. It is a process that starts on paper and with paper, that uses drawing as its ally and not the antagonist of color. It is also able to define the physical dimension of a flat material, clipping it out and building structures that suggest those of a sculpture. Movement does not remain alone in the eyes of the beholder, but it enters the physical structure that inhabits space, hovering from the ceiling, disputing Dalí’s attacks on Calder again. “The minimum one can ask a sculpture is to stay still”, like a form that reproduces itself in various expressions of matter, even becoming a moving image onscreen. Painting, however, is also conveying information through a gesture, a thought that inhabits and runs all over the body until it meets the canvas, where it is obvious that there is nothing deeper than the skin, as Paul Valéry said once. This is because, on the shiny surface of the canvas, we can preserve the peculiarities of color, an otherness whose complexity exceeds the tools we usually use to describe the world, but also the possibility to glimpse other worlds that would not be possible any other way.

Sonia Fernández Pan

(This text was written for the publication of the exhibition HISK Laureates 2017: The Grid and the Cloud. How to Connect. in 2017.)